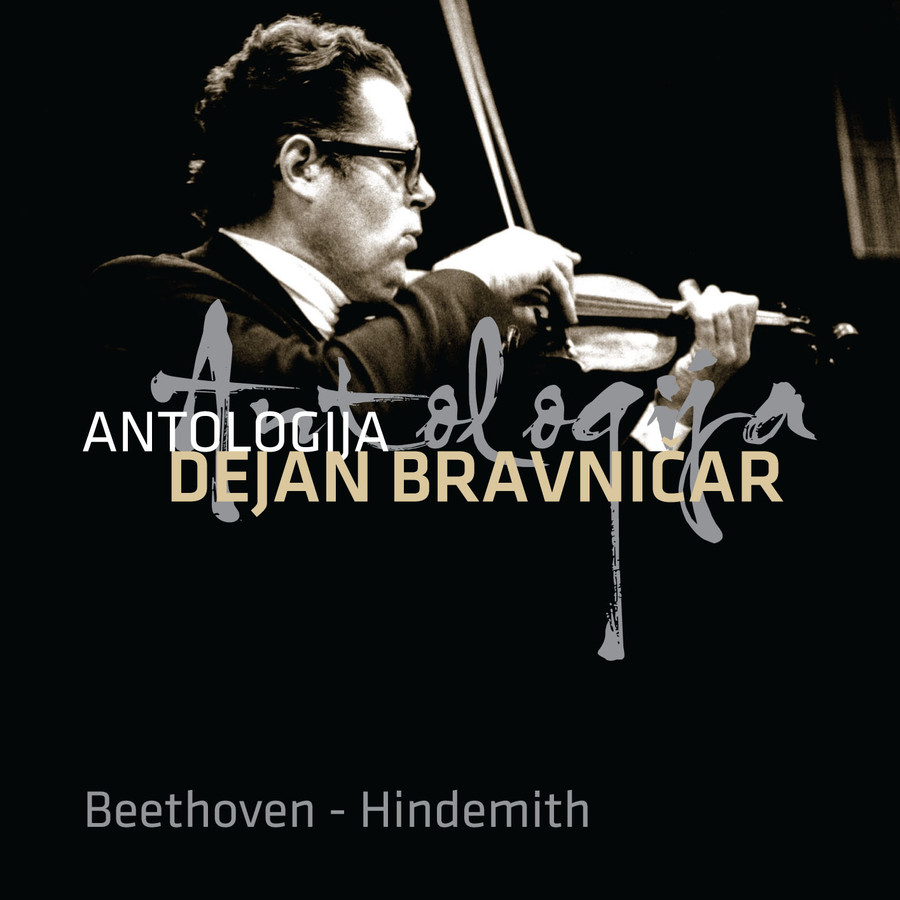

DEJAN BRAVNIČAR

ANTOLOGIJA - DEJAN BRAVNIČAR: BACH, MOZART, BEETHOVEN, STRAVINSKI

Classical and Modern Music

Format: CD

Code: 114748

EAN: 3838898114748

Three hundred years after their creation, Johann Sebastian Bach’s solo violin compositions still rank among the greatest achievements of this genre. The composer wrote three sonatas and three partitas for solo violin. Among the partitas, the second occupies a special place, mainly due to the final movement, Ciaccona. Yehudi Menuhin called it “the most magnificent composition ever written for solo violin”, while Joshua Bell claimed that the movement

“is not only one of the greatest musical works of all time, but also one of the greatest achievements of an individual in the history of mankind. The work is spiritually powerful, emotionally powerful and formally perfect”.

Although questioned by some experts, musicologist Helga Thöne associates the creation of the composition with a tragic event in the composer’s life, when he returned home from a long journey only to find that his first wife, Maria Barbara Bach, had died during his absence. The Ciaccona is thought to be her “tombeau” or tombstone.

The Baroque partita is a cyclic instrumental composition consisting of various dance movements. Partita No. 2, BWV 1004 contains five such movements, with the Italian designations Allemanda, Corrente, Sarabanda, Giga and Ciaccona.

The chaconne originates from a light, lively Latin American dance, which, in the sixteenth century, evolved into a slow instrumental composition with a triple metre. Based on a repeating bass melody, it is closely related to the passacaglia. The chaconne emerged from Spain as guitar music and spread throughout Europe. Two models eventually took shape, the French and the Italian, which differ primarily in the treatment of the bass line. In the chaconne from the

second partita, Bach mainly followed the Italian model, using a strict ostinato bass technique in which the bass line undergoes extensive figuration in sixty-four variations, sometimes to the point of becoming unrecognisable.

In the spring of 1784, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart performed at least four times a week for various Viennese nobles or at subscription concerts. In addition to some twenty-two performances in five weeks, he still managed to teach and compose. During this time, the twenty-two-year-old violin virtuoso Regina Strinasacchi asked him to collaborate in a concert, as well. Mozart was charmed by her playing and could not refuse her request. Since, at that

time, it was customary to perform new works at concerts, Mozart had no choice but to write a new composition for the occasion. According to Mozart’s wife Constanze, the composer only provided the violinist with her solo part the evening before the concert, giving her very little time to practise it before the performance. However, he did not mention the fact that he had not yet been able to write the piano part. At the concert on 29 April, the two musicians performed without rehearsal. Mozart

played the piano on the basis of the written violin part and a few sketched modulations. He did, of course, try to conceal this fact, but Emperor Joseph II noticed through his theatre glasses that Mozart was playing from a blank sheet. He therefore ordered Mozart to call on him after the concert, instructing him to bring the manuscript of the new composition with him. Mozart had no choice but to admit to the Emperor that he not yet been able to write the piano part. Rather than being upset,

however, the Emperor was highly amused.

The sonata has three movements. The first, marked Largo – Allegro, begins with a very slow introduction, in which the equality of both instruments is established, a feature that was not at all self-evident at the time, and that is maintained throughout the work. The second movement is an expressively profound Andante. It was initially conceived as an Adagio, but Mozart later changed his mind. The work is rounded off with a refined rondo, marked Allegretto. The sonata represents one of the

pinnacles of Mozart’s creativity in the field of chamber music.

In addition to the piano, Ludwig van Beethoven also played the violin and the viola. He learned to play string instruments at home in Bonn, but continued his studies in Vienna with the renowned violinist Schuppanzigh. In the period 1797–1798, he wrote the first three violin sonatas, Op. 12 for “piano and violin”, as they were usually called in those times. He dedicated them to court composer Antonio Salieri, with whom he studied dramatic and vocal

composition.

These first violin sonatas were not received favourably by critics, with one critic writing that they were “lost in the forest”. They were labelled “eccentric”, “unnatural” and even “perverted”. They sounded too unusual for contemporary ears. Viewed from today’s perspective, however, they seem both conventional and novel at the same time. On the one hand, Beethoven provides a condensed summary of the achievements of the high classicalism of Haydn and Mozart; on the other hand, he imbues the

sonatas with his distinctly personal emotional seal, as reflected in the boldness (for the time) of the modulations to distant keys, the unconventional distribution of accents, and so on. It is precisely this emphasised expression, which departs from classical calmness, that most likely shocked critics.

The first of the three sonatas is written in D major and has three movements. The first movement, Allegro con brio, emerges from the richness of the selected musical material. The composer demonstrates his extraordinary skill in the exchange of the roles of the two instruments. The equal role of both instruments is in fact a feature of all three sonatas. The second movement replaces the usual Adagio or Andante with a theme and variations (Tema con variazioni:

Andante con moto), while the third movement is a lively Rondo: Allegro in which the harmonic development from the first movement resounds, thus binding the movements even more tightly and rounding the work out as a whole.

With his first sonatas for violin and piano, Beethoven already demonstrated his mastery of the genre.

The path to the Suite italienne for violin and piano (1933) by Igor Stravinsky was long. It began as early as in 1919 with an idea of Sergei Diaghilev, the impresario of Ballets Russes, to create a new ballet entitled Pulcinella based on characters from commedia dell’arte and the music of Neapolitan Baroque composer Giambattista Pergolesi. At first, Stravinsky was apparently not very enthusiastic, but he reconsidered after studying the scores

found by Diaghilev in Neapolitan and London libraries. He was inspired by the themes and textures of the early music, which he equipped with modern rhythms and harmonies, giving rise to the Neoclassical style in music. The ballet was staged with great success in May 1920 in Paris, with choreography by Léonide Massine and stage scenery and costumes by Pablo Picasso.

Stravinsky was fond of making arrangements of his own compositions. As with the previous ballets, the material from Pulcinella was first used for an eponymous orchestral suite. This was followed by the Suite after Themes, Fragments and Pieces by Giambattista Pergolesi for violin and piano, written in collaboration with Polish violinist Paul Kochanski. In 1932, in collaboration with cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, the ballet music was arranged as the Suite italienne for cello and piano, which

then served as the basis for the Suite italienne for violin and piano, in which Stravinsky was assisted by violinist Samuel Dushkin.

The suite has six movements: Introduzione, Serenata, Tarantella, Gavotta con due variazioni, Scherzino and Minueto e finale. At the time of the creation of the ballet, neither Stravinsky nor Diaghilev was aware that not all of the music they had attributed to Pergolesi was in fact the work of the Neapolitan master. The Introduzione, Gavotta and Finale are actually based on works of Pergolesi’s contemporaries Domenico Gallo and Carlo Monza, a fact that was only

discovered by later research.

Dr. Borut Smrekar

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750):

Partita for Solo Violin No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004

1 V Ciaccona 15:24

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791):

Sonata for Violin and Piano in B flat major, KV 454

2 I Largo-Allegro 7:19 (listen!)

3 II Andante 8:24

4 III Allegretto 7:00

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827):

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1 in D major, Op. 12 No. 1

5 I Allegro con brio 8:47

6 II Tema con variazioni: Andante con moto 7:10

7 III Rondo: Allegro 4:31

Igor Stravinski (1882-1971):

Suite italienne for violin and piano

8 I Introduzione 2:23

9 II Serenata 3:23

10 III Tarantella 2:12

11 IV Gavotta con due variazioni 3:28

12 VI Minuetto e finale 4:32

Dejan Bravničar, violin

Aci Bertoncelj, piano

Marijan Lipovšek, piano

Recorded: Slovenska filharmonija, 1964 (5-7), 1992 (1-3), Radio Slovenija, Studio 13, 1979 (8-12), Radio Slovenija, Studio 14, 1999 (1).